Understanding CNIPA Stricter Trademark Examination Policies and Their Impact on Brands

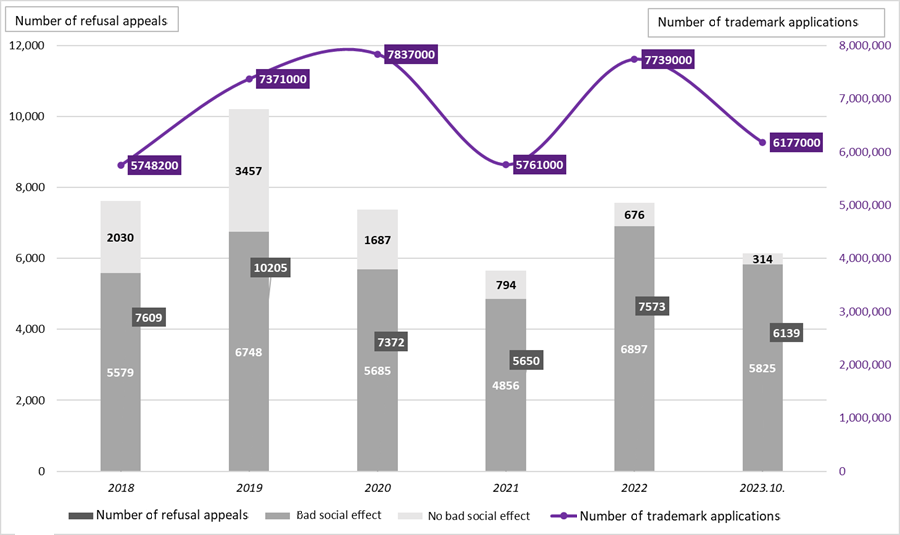

From 2024, the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA), which oversees the Trademark Office (TMO) and the Trademark Review and Adjudication Board (TRAB), introduced significantly stricter examination criteria for new trademark applications. This policy change has led to a notable increase in refusals based on absolute grounds, as well as more frequent objections citing prior trademarks. This rigorous approach reflects CNIPA goal to reduce the annual number of trademark registrations in China, thereby strengthening the quality and distinctiveness of the trademark register.

Since these enhanced standards were implemented, brand owners have faced a growing number of refusals that sometimes seem arbitrary or inconsistent with past practices. Particularly challenging are cases where applicants already hold valid registrations for identical textual marks in China and seek to protect new stylized versions of the same marks. Such refusals not only hinder brand development but also represent a shift from previous examination norms.

This article offers a detailed analysis of the legal basis for refusals grounded in absolute grounds, recent changes in CNIPA examination practices, risks associated with using unregistered marks previously denied protection, and the broader implications of CNIPA stricter policies for existing registrations and commercial operations in China. Given these developments, it is essential for brand owners to carefully consider the significantly increased risk of refusal before submitting new applications or reapplying for existing marks. While appeals against unfavorable decisions remain an option, both the TRAB and Beijing courts have shown a tendency to uphold TMO rulings, likely reflecting alignment with overarching policy objectives.

Legal Framework and Background for Trademark Refusals in China

The absolute grounds for refusing trademark applications are outlined in Articles 10 and 11 of the PRC Trademark Law. Article 10 prohibits the use and registration of trademarks that harm state interests, public order, or social morality. This includes marks that may damage national dignity, public interests, social stability, national unity, religious beliefs, or have other adverse effects. Specific exclusions cover trademarks featuring state symbols such as national flags or emblems, as well as those deemed harmful to society—for example, marks that are racially discriminatory, deceptive, politically sensitive, or likely to cause negative social consequences. Article 11, on the other hand, forbids the registration—but not the use—of trademarks lacking inherent distinctiveness, meaning they cannot fulfill the essential function of identifying the source of goods or services. A key principle in examination is that if the verbal element of a composite mark lacks distinctiveness, the entire mark will be considered non-distinctive unless the textual part is merely incidental to the overall design.

Recent Changes in CNIPA Trademark Examination Practice

As noted, CNIPA has adopted a more stringent approach to assessing trademark registrability, consistently reflected in decisions by both the TMO and TRAB. Judicial bodies have also shown less willingness to overturn CNIPA refusals based on absolute grounds, indicating a unified policy stance across administrative and legal channels.

Suggestive trademarks have been particularly affected by these tightened standards. Commercially, effective trademarks often subtly hint at product characteristics, aiding consumer recognition while maintaining distinctiveness. Historically, suggestive marks have balanced these aspects well—for example, Safeguard for soap, 帮宝适 (the Chinese equivalent of Pampers, meaning helping infants feel comfortable), and 汰渍 (the Chinese mark for Tide, meaning eliminating stains) were commonly approved.

Recently, however, the TMO has become more reluctant to approve the registration of suggestive trademarks, frequently classifying them as descriptive and thus lacking distinctiveness, or as deceptive when verbal elements might exaggerate product attributes. Additionally, marks referencing product names, colors, or other features, or containing advertising language—even if only loosely related to the goods or services—face increased refusal risks, regardless of other distinctive elements or indirect associations.

Moreover, the TMO has broadened the use of unhealthy social effects as grounds for refusal. CNIPA is believed to maintain a confidential list of prohibited words and characters, likely including terms such as 国 (nation), 华 (China), and 中 (center). Examiners may also apply unconventional interpretations or homophones to assign negative meanings to otherwise neutral marks, leading to refusals based on tenuous or speculative connections. While successful appeals against refusals citing unhealthy social effects have occasionally occurred, such outcomes are rare. In contrast, challenging refusals based on deceptiveness has proven significantly more difficult at all levels of appeal.

Risks of Using Unregistered Trademarks in China After Refusal

For marks refused under Article 11 due to lack of distinctiveness, continued unregistered use is legally permitted. Such marks may eventually qualify for registration if they acquire distinctiveness through extensive use. However, the standard for proving acquired distinctiveness in China is notably high. Applicants must provide substantial evidence of long-term, widespread use across China, demonstrating that the relevant public directly associates the mark with the applicant. A notable example is the U.S. cosmetics brand FRESH, which overcame a distinctiveness refusal by submitting comprehensive evidence of sales and advertising in multiple Chinese cities over many years, including advertisements in leading Chinese media. Nonetheless, during the period when the owner is building the mark reputation, significant infringement risks remain. These risks arise not only from conflicting registered marks but also from the possibility that third parties may register identical or similar marks despite prior refusals of the legitimate owner applications. This inconsistency results from CNIPA case-by-case examination approach, which allows examiners to disregard outcomes in similar cases, treating each application independently.

For marks refused under Article 10 due to deceptiveness or potential to mislead, the risks are considerably greater. Unlike Article 11, Article 10 prohibits both registration and use of such marks. Infringements can lead to administrative penalties, including fines up to 20% of the turnover related to the offending mark. Historically, enforcement against use of such marks has been relatively lenient. However, CNIPA in May 2023 announced proactive market monitoring to detect use of marks previously refused under Article 10, especially those deemed deceptive or socially harmful. Risks increase when applicants submit evidence of use in China to contest refusals, potentially alerting authorities to infringing activities.

Given these risks, when there is a tangible chance that a mark may be refused under Article 10, stakeholders should consider alternative strategies tailored to the Chinese market. These might include redesigning the mark—possibly adopting a dedicated Chinese brand—filing applications under unrelated third parties, avoiding traditional trademark use, or limiting use to trade names or advertising slogans where legally permissible.

Potential Effects of Stricter Examination on Existing Trademark Registrations

Over the past three to five years, CNIPA and the courts have taken a firmer stance against trademark piracy. In response, bad-faith actors have shifted from passive tactics to more aggressive strategies, such as filing retaliatory non-use cancellation actions against vulnerable registrations owned by their targets to pressure settlements. Alarmingly, CNIPA stricter interpretation of registrability standards may encourage squatters and other bad-faith parties to initiate invalidation actions against existing registrations, claiming these were void from the outset due to inherent defects under Articles 10 or 11. So far, TRAB and courts have generally sided with rights holders in these cases, dismissing invalidation petitions and upholding registrations. This supportive approach is especially evident when the contested trademark has limited distinctiveness but has been extensively used and has acquired reputation in China, and when the petitioner is found to have acted in bad faith.

Recent examples include invalidation actions against the marks CELLFOOD (covering nutritional preparations in Class 5) and HEATSTICKS (covering electronic cigarettes and accessories in Class 34) brought by squatters and competitors. In both cases, TRAB upheld the registrations, reasoning that the marks were coined terms rather than common names or direct product descriptions, despite suggestive meanings. TRAB also recognized the significant reputation built through continuous use and promotion. In the CELLFOOD case, TRAB explicitly condemned the petitioner bad faith, noting the invalidation action supported the petitioner own piratical applications for similar marks.

Given these risks, companies should proactively identify and address vulnerabilities in their trademark portfolios, especially when considering enforcement actions against large-scale infringers who may retaliate with invalidation claims as their illicit portfolios lose value.

Final Thoughts on Navigating China Evolving Trademark Landscape

Despite efforts by various stakeholders to advocate for changes to CNIPA examination practices regarding absolute grounds, current feedback suggests little chance of near-term reform. CNIPA position indicates that the rigorous examination regime will continue for the foreseeable future. Therefore, businesses operating in China—particularly multinational corporations introducing offshore products and trademarks—must remain vigilant. Some trademarks may ultimately be deemed unregistrable or even prohibited from use in China. This reality calls for more comprehensive clearance searches and risk assessments focused on potential Article 10 and 11 objections early in the trademark planning process for the Chinese market.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. Given the rapidly evolving nature of trademark practice in China, readers are strongly encouraged to consult qualified legal professionals for guidance on specific cases or strategies.