AI models comprise their structure and parameters. The structure includes the arrangement and quantity of components, while the parameters are specific values obtained through training and optimization.

In March 2025, the Beijing Intellectual Property Court made a landmark ruling in the Douyin v. B612 case, marking the first time AI model structure parameters were protected under unfair competition law. Concluding on March 31, 2025, this case has significantly impacted the industry and is the first in China concerning AI special effects model rights.

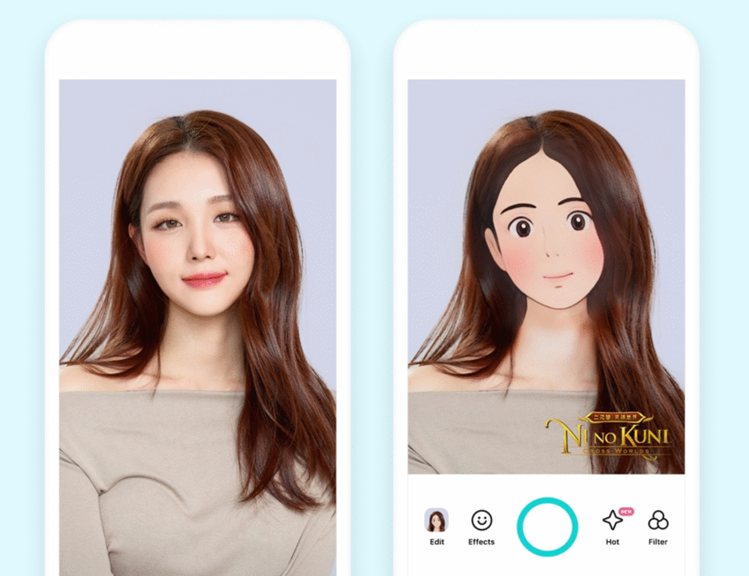

In the lawsuit filed by China Douyin against Yiruike for AI model infringement, Yiruike utilized Douyin’s cartoon transformation effect model without permission. This breached commercial ethics, violated Douyin’s rights, disrupted fair market competition, and harmed consumers. The court affirmed that AI model structure and parameters are protectable competitive interests under unfair competition law.

I. AI Models and Copyright Protection: Key Considerations

The Beijing Chaoyang District People’s Court, in its initial ruling, clearly stated that AI models are not eligible for copyright protection. In this case, Douyin Company argued that comic imaging qualifies as artistic or audiovisual work, involving four stages—style setting, stylized mass production, model training, and user generation—that reflect the company’s original creative decisions. However, the court simplified these into two main phases: model training and model generation.

The court emphasized that model training is essentially a technical process focused on developing tools, which does not meet the creative criteria required for copyright protection. It noted that copyright law does not protect mere accumulation of materials, data, or the creation of tools, nor does it cover mechanical processes that follow established rules without room for creativity. From a technical standpoint, style setting and mass production are part of data accumulation for training AI models, while model optimization is the creation of generation tools. Accordingly, the court applied the “creation tool theory,” viewing AI models as technical tools rather than creative works.

Furthermore, users employing AI creation tools do not contribute original creative input. The process of generating images through special effects tools is considered a technical operation without the originality required by copyright law. User inputs, such as portraits used as prompts, lack personalized artistic choices and are mechanical reproductions of existing images, failing to qualify as protected works. Similarly, the AI-generated outputs do not meet originality standards due to the unpredictable and random nature of the transformation from input to output. While courts in other AI-generated content cases have acknowledged AI’s role alongside limited human control, this case uniquely recognized a limited correspondence between user input and AI output. Since the input lacks originality and the output closely corresponds to it, the generated content also lacks the originality necessary for copyright protection.

II. Prioritizing Competition Law in AI Model Governance

Competition law offers a clear and effective legal framework for regulating AI model development and use. By defining acceptable market behaviors, it helps prevent abuse of dominant positions and ensures fair competition, fostering a stable environment conducive to innovation in AI technology.

In the appeal heard by the Beijing Intellectual Property Court, the court endorsed applying competition law to AI models, recognizing that model architecture and parameter configurations are core technological innovations deserving legal protection. The court found that the defendant’s imitation of Douyin Company’s “Comic Transformation” AI model through the “Girl Comic” model constituted unfair competition. Key points included: both parties competing directly in the anime special effects market; the original model’s early release and user base providing significant competitive advantage; the defendant’s lack of independent development evidence; and the high similarity and substitutability of the competing models, which harmed Douyin’s market position.

The court highlighted that the essence of protecting competitive interests lies in the internal structure and parameters of AI models rather than their external product manifestations. Since AI-generated outputs do not always reflect internal model mechanisms, infringement assessments require detailed analysis of model architectures and parameters. Identical models may produce different outputs due to training variations, while different models can generate similar results through techniques like knowledge distillation. Partial overlaps in model design further complicate infringement determinations, especially given the “black box” nature of AI models and potential modifications that mask dependencies on original models.

Therefore, legal evaluations of AI model infringement should go beyond surface-level product comparisons and focus on substantive examination of internal model mechanisms. Introducing a substantial substitution standard under competition law allows assessment of whether an infringing model impacts the original’s market share and user engagement, effectively deterring free-riding and promoting healthy competition and innovation. With its adaptable regulatory approach and emphasis on fair competition, competition law provides a technically sound and practical framework for addressing potential misuse of AI technological achievements.