Introduction: Navigating a Commercial Paradox in China Retail Landscape

In the bustling shopping centers of Shanghai and Beijing, consumers witness a unique intellectual property scenario unfolding firsthand. Two separate companies operate stores under the identical MUJI brand—Japan Ryohin Keikaku Co., Ltd. (Authentic MUJI) and Beijing Cottonfield Textile Co., Ltd. (Chinese MUJI)—located just meters apart yet entirely independent. In July 2025, the Supreme Court landmark ruling affirming Beijing Cottonfield Class 24 无印良品 trademark right (covering towels, textiles, and bedding) concludes a 24-year legal battle and highlights key insights into China evolving IP environment.

The Japanese MUJI brand journey in China sets important precedents for international brands navigating China first-to-file trademark system, illustrating both the risks of delayed registration and the legal framework enabling brand coexistence.

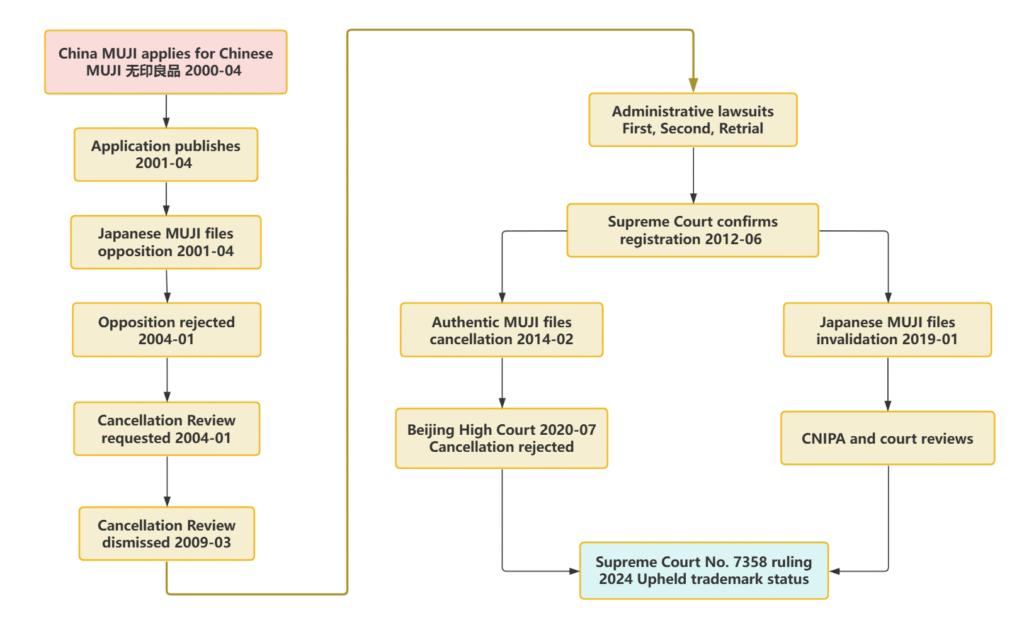

Overview of the complex 无印良品 Trademark Procedures

The trademark conflict between two MUJIs over the “MUJI” trademark has spanned 24 years, involving three key stages: opposition, non-use cancellation, and invalidation proceedings initiated by the Japanese side, Authentic MUJI.

- April 6, 2000: China MUJI applies to register the Chinese MUJI 无印良品 trademark.

- April 28, 2001: Trademark Office preliminarily approves and publishes the trademark (Class 24: cotton textiles, towels, quilts, bath towels, etc.).

- April 26, 2001: Authentic MUJI files an opposition.

- January 7, 2004: Trademark Office rejects the opposition.

- January 29, 2004: Japanese party requests a review.

- March 2009: Trademark Review and Adjudication Board dismisses the review.

- June 29, 2012: Supreme Court confirms that the Chinese “MUJI” trademark should be registered (after first-instance, second-instance, and retrial administrative lawsuits).

- February 2014: Authentic MUJI seeks to cancel the Chinese “MUJI” trademark, citing non-use for three consecutive years.

- July 30, 2020: Beijing Higher People’s Court rules in the second instance that the registration announcement date should be considered as November 28, 2016 (because the opposition was filed before the publication). Therefore, the cancellation request in February 2014 was premature and rejected.

- January 2019: Japanese company files for invalidation of the trademark.

- 2024: Supreme Court upholds the legal validity of the Chinese MUJI 无印良品 trademark (administrative ruling No. 7358).

Why the Class 24 无印良品 Belongs to China MUJI

According to the Supreme Court 2024 administrative ruling No. 7358, the primary reason for rejecting the Japanese party claim to invalidate the Chinese MUJI trademark was that most of the evidence they provided regarding promotional use was either produced outside China or after the trademark application date. There was insufficient proof that goods bearing the MUJI mark had entered mainland China before the application date. The promotional materials submitted during the retrial, such as newspapers and journals, mainly reported on the MUJI brand but did not specifically relate to the Class 24 goods (cotton textiles, etc.) under dispute. Therefore, the claim that MUJI had been used and had influence on Class 24 goods lacked factual support.

Historical Background: Origins of a Two-Decade Trademark Dispute

Early Market Entry Challenges (1980–2004)

Ryohin Keikaku introduced its innovative no-brand quality goods concept in Japan in 1980 and expanded cautiously, opening its first overseas store in Hong Kong in 1991. However, during its extended preparation to enter mainland China, the company delayed registering trademarks in critical product categories.

Meanwhile, in April 2000, Hainan Nanhua Industrial Trading Company filed for the MUJI trademark in Class 24 (textiles), which was approved in 2001. Ownership later transferred to Beijing Cottonfield in 2004, a textile-focused company established to capitalize on this branding opportunity. Ryohin Keikaku opposition in 2001 sparked a multi-generational legal dispute.

Despite persistent appeals and challenges over 23 years, Chinese courts consistently upheld Beijing Cottonfield priority based on the first-to-file principle, noting Ryohin Keikaku insufficient brand recognition in mainland China before 2000. This sequence laid the groundwork for the current dual-brand marketplace.

Parallel Business Development and Expansion

Following the legal stalemate, both companies pursued strategic growth. Authentic MUJI expanded methodically, opening its first mainland store in Shanghai in 2005 and growing to 414 outlets across 81 cities, cultivating a premium brand image. Concurrently, Beijing Cottonfield leveraged its trademark rights to build vertically integrated operations, including over 200 physical stores styled similarly to Japanese MUJI, 300 online shops, and twelve subsidiaries using variations of the MUJI name, generating approximately four billion RMB in 2024 revenue primarily from home textiles. This parallel development intentionally created marketplace ambiguity, leading to inevitable consumer confusion.

Chinese MUJI Online Stores

Chinese MUJI Stores in Shopping Malls

Japanese Authentic MUJI Stores

Legal Framework: Key Litigation Milestones in China Judiciary

Four-Stage Legal Progression

The trademark dispute evolved through distinct phases reflecting China IP legal maturation. Initial administrative rulings (2000–2004) favored Beijing Cottonfield despite Ryohin Keikaku opposition. Over the next decade, courts consistently rejected appeals challenging the trademark on grounds of bad faith or international fame. In 2022, the Beijing Higher Court ruled against Beijing Cottonfield retail entities for unfair competition while affirming their textile trademark rights, establishing a nuanced coexistence precedent. The Supreme Court 2024 denial of Ryohin Keikaku’s final retrial request conclusively ended the dispute.

Judicial Reasoning and Evidentiary Standards

Throughout appeals, courts rigorously applied China trademark laws and evidentiary requirements. Ryohin Keikaku alleged deceptive registration and sought protection based on international reputation. However, courts found insufficient evidence of brand recognition in China prior to 2000, requiring authenticated consumer surveys, advertising records, or media coverage to substantiate claims. Without such proof, allegations of trademark squatting were legally unsubstantiated. Additionally, courts acknowledged Beijing Cottonfield investments in manufacturing and supply chains as indicators of legitimate commercial interest rather than bad faith.

Consumer Impact: Confusion and Corporate Responsibility

Market Confusion Data

Research commissioned by consumer protection groups highlights ongoing confusion: 42% of surveyed Shanghai shoppers mistakenly attributed Beijing Cottonfield products to the Japanese MUJI brand. Online, over 17,000 social media complaints about fake MUJI surfaced in 2023 alone. The use of identical Chinese characters (无印良品) and nearly indistinguishable store designs—featuring minimalist wood fixtures and beige palettes—further contribute to consumer uncertainty.

Brand Responses

Both companies have taken steps to address this confusion. Beijing Cottonfield introduced corporate name changes for subsidiaries, added Nature Mill branding in stores, and included online disclaimers, though packaging still prominently features MUJI. Ryohin Keikaku adopted MUJI No Brand composite branding, differentiated store signage with bilingual labels and location details, and invested in consumer education via digital platforms. Despite these efforts, both continue to operate under the same core brand identity within legally permissible but confusing boundaries.

Implications for International Trademark Strategy in China

Systemic Challenges Highlighted

The MUJI case underscores structural challenges for foreign brands entering China. The absolute first-to-file system prioritizes timely registration over prior use or international fame. Class-specific trademarks allow divided rights across product categories, and separate retail service trademarks enable distinctions between stores and merchandise, as seen here. Court strict demand for documented pre-filing market recognition contrasts with common-law jurisdictions that recognize unregistered rights.

Recommended Protective Measures

Legal advisors should adopt comprehensive strategies tailored to these realities. Early and broad trademark registration across all relevant classes—ideally five years before market entry—is essential. Building China-specific evidence of brand recognition through trade show participation, notarized documentation, distributor agreements, media coverage, and consumer surveys is critical. Prompt opposition filings within the three-month window after trademark publication are necessary to challenge conflicting applications. For established brands facing divided rights, coexistence agreements with clear usage parameters may offer practical solutions over protracted litigation.

Conclusion: Trademark Development in China Evolving Legal Environment

The Supreme Court ruling closes a historic chapter while allowing both MUJI entities to operate within defined spheres—Beijing Cottonfield dominating textile wholesale and Ryohin Keikaku maintaining premium retail presence. This prolonged dispute reflects the maturation of China IP judiciary, balancing trademark statutes with unfair competition principles and emphasizing brand owners duty to minimize consumer confusion. Foreign companies must recognize that China IP system operates differently from Western models; trademark registration is foundational but must be complemented by distinctive branding, retail experiences, and transparent narratives. Authentic MUJI resilience despite trademark setbacks demonstrates that global brands can thrive without exclusive naming rights when supported by quality and cultural relevance. As noted by the Beijing Higher Court, trademark law ultimately serves the goal of fair competition rather than existing as an end in itself.