A recent decision by the Shanghai Intellectual Property Court offers a vital lesson for international brand owners and their Chinese partners. The court overturned a lower court ruling in a trademark licensing dispute (referred to here as the Brand A Case), dismissing the plaintiff claims entirely. This case, centered on a sub-licensing arrangement involving a foreign brand in China, exposes common legal pitfalls and provides valuable insights on structuring such agreements to minimize risk.

As counsel for the successful party on appeal, I will review the key issues and share practical strategies for risk prevention.

I. Overview of the Case

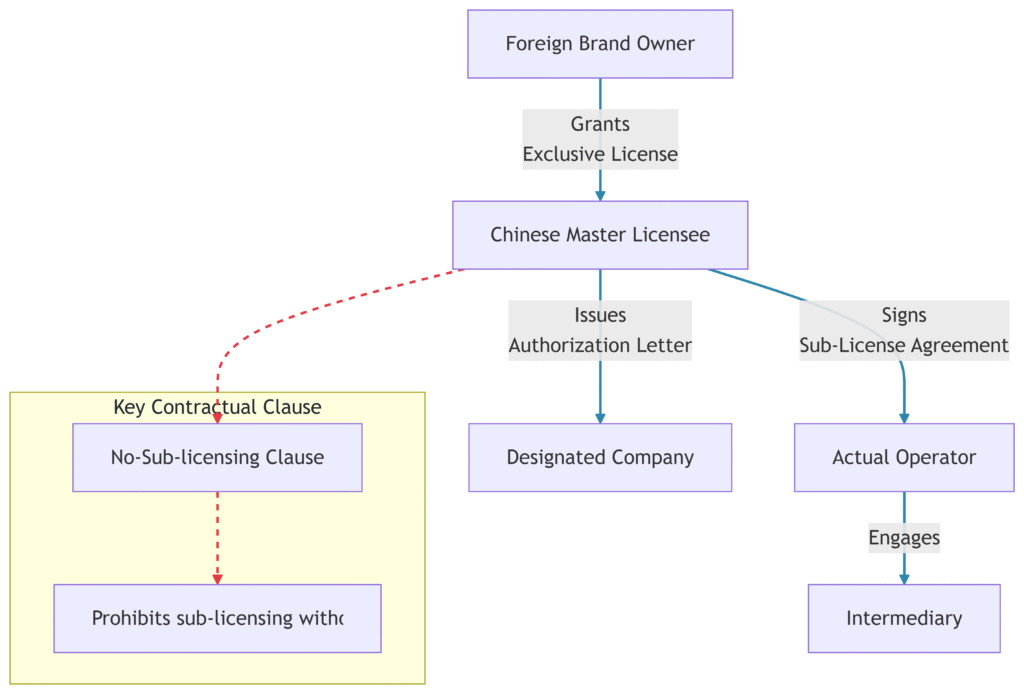

In October 2018, the Operator (Party A) engaged an Intermediary (Party C) to facilitate a cooperation agreement with the owner of Brand A and authorized the Intermediary to handle payments on its behalf. In November 2018, the Master Licensee (Party B) entered into a License Agreement with the foreign Brand Owner for the use of Brand A registered trademark in China. This agreement included a critical No-Sub-licensing Clause, explicitly prohibiting the Licensee from sub-licensing or transferring rights without prior written consent from the Brand Owner.

Shortly thereafter, the Master Licensee and the Operator signed a Brand Agreement, authorizing the Operator to manufacture and sell products under Brand A. The Operator paid RMB 5.55 million for intermediary fees and licensing rights. At the Operator request, the Master Licensee coordinated with the Brand Owner to issue an authorization letter permitting a designated company (Company D) to operate online stores on platforms such as Tmall, JD.com, and Vipshop.

The Operator later sought to rescind the Brand Agreement and demanded a refund of RMB 4.25 million plus interest from the Master Licensee and Intermediary. The first-instance court ruled in favor of the Operator, finding that the Master Licensee had concealed the No-Sub-licensing Clause, constituting fraud, and ordered a refund.

However, the Shanghai Intellectual Property Court reversed this decision on appeal. Key evidence showed that the Master Licensee had provided both Chinese and English versions of the master license agreement—including the No-Sub-licensing Clause—to the Intermediary before the Brand Agreement was signed. Based on this, the appellate court found no sufficient evidence of fraud and dismissed all claims.

II. Common Legal Risks in Foreign Brand Licensing in China

Foreign brands typically enter the Chinese market through a two-tier licensing structure:

- Tier 1: The foreign Brand Owner grants an exclusive license to a Chinese master licensee.

- Tier 2: The master licensee appoints brand operators to manage the business.

Brand Owners often include a No-Sub-licensing Clause in master agreements to maintain quality control, approving sub-licenses on a case-by-case basis. The Brand A Case highlights that the greatest legal risks arise in the second tier—the relationship between the master licensee and the operator.

Key risks include:

- Disputes over the operator status—operators may seek total agent or exclusive general agent status for broader rights, conflicting with their legal role as sub-licensees. This mismatch often leads to disputes, as seen in the Brand A Case.

- Challenges to the validity of sub-licensing agreements—operators may allege fraud or lack of authority if the master license prohibits sub-licensing, risking contract invalidation.

- Payment disputes and breach liability—long-term staged payments and penalty clauses for default can become contentious if the relationship deteriorates.

III. Proactive Risk Prevention Strategies

The appellate ruling in the Brand A Case offers clear guidance for avoiding such disputes:

- Clearly define the operator role in the contract—only the written agreement governs rights and obligations. Any informal claims to total agent status must be explicitly included to have legal effect.

- Ensure transparency and fulfill obligations—disclose key master license terms, especially the No-Sub-licensing Clause, before signing to prevent fraud claims. Also, secure necessary authorizations from the Brand Owner during performance to demonstrate legitimacy.

- Enforce contract rights promptly and reasonably—act decisively if payments are missed, but ensure penalty clauses comply with Chinese law, which requires damages to be foreseeable and not punitive.

IV. Conclusion: A Framework for Secure Brand Licensing in China

The primary risks in foreign brand licensing in China arise between the master licensee and the brand operator. To protect all parties’ interests, it is essential to:

- Disclose key upstream license terms and draft clear, precise sub-license agreements before signing.

- Follow the commercial model carefully and obtain necessary authorizations during contract performance.

- Respond swiftly and lawfully to breaches to minimize financial impact.

The Brand A Case underscores that in China complex legal environment, well-drafted contracts, transparent communication, and diligent performance are not just best practices—they are critical safeguards against costly disputes.